Footloose, Even In An Army Uniform

On the road…again!

Afghanistan to Zambia

Chronicles of a Footloose Forester

By Dick Pellek

In the Army

As a draftee, the Army experience of the Footloose Forester was different from what many civilians might perceive as a typical military tour of duty. He was called to duty when he was living in Nevada City, California and he reported to Oakland, California for a physical exam and eventual induction into the US Army. In those days the military draft was still in effect, so as a 22-year-old graduate from a college in New Jersey, he had to keep the Selective Service Commission informed of any changes of addresses. He dutifully sent them written correspondence about his many changes of address, especially the big one from New Jersey to California.

Most people believe that you can never change your official Home of Records, but he knew that such an official change was not only possible but probably inevitable for him. By that time, he was already on his way to becoming the Footloose Forester. Having moved 26 times in six months after graduating from college, he knew that keeping the official record clean was his responsibility; furthermore, he wanted to return to California after military service, in the event that he was drafted. So, it transpired, that residents of Nevada City reported to the Nevada County Court House for processing.

After he returned from active duty, it would take more than two full years to prove to the US Army that Nevada City, in Nevada County, California was his new and official Home of Records, and not Morristown, New Jersey where he had registered for the draft when he was 18 years old. He knew the rules and followed them, as regards registering and then changing his address, not that anybody in the Army would listen to him or even follow the cited law that was written down in an official Army publication.

Footloose Forester enjoyed his years in the Army. But he did not enjoy the Army or its lifestyle, nor the company of most of the people who thought of themselves as heroic figures in an honorable profession. Truth be known, many, too many, soldiers he knew were dim-witted dropouts from high school or from other, more challenging callings. It would not be fair to generalize because there were just enough real heroes, survivors from World War II and the Korean War that still wore the uniform to make blanket statements about the soldiers around him. Even discussing it openly was a rather rash idea. He respected those who bore the scars of combat, and most of the officers he knew. He was lucky enough to serve with a handful of West Pointers and all of them were outstanding soldiers in every respect.

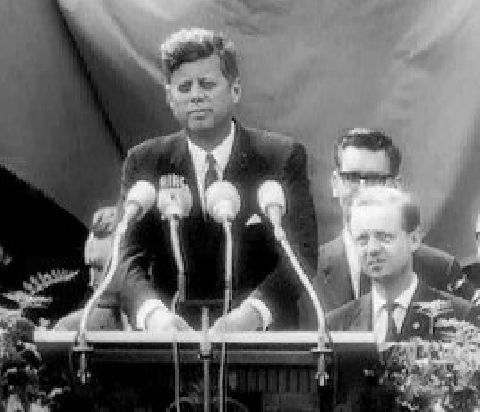

JFK in Berlin the day before he visited Fliegerhorst Kaserne

On the other hand, many of his enlisted counterparts resented him because he had a friendly, but the unacknowledged relationship with the Battalion Commander and with the Company Commander in Germany. Why would that be a problem? Because there presumably was no trespassing of enlisted men into officer’s clubs, mess halls, and social venues. Yet, Footloose Forester was invited to their clubs on more than one occasion, and for that, he was roundly vilified. Many decades after his Army years, he still remembers that the most fruitful working relationships that he had were with the Battalion Commander and the young Company Commander, a West Pointer whom he later visited after he retired to Virginia. Captain Wally Ward nominated Footloose Forester to represent our unit at the luncheon for President John F. Kennedy at Fliegerhorst Kaserne, in Langendiebach, Germany, the day after the President’s famous “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech in 1963.

Of course, being selected over others with long service records and those soldiers who had enlisted, earned him a ton of resentment from his fellow soldiers. But part-and-parcel of being selected to have lunch with John F. Kennedy was because Footloose Forester had earned so many points for outstanding performance.

At one time or another, he was recognized as the Colonel’s Orderly a dozen different times. That honor merely implied that he was adjudged as the best dressed, best responding candidate with the shiniest boots when we were summoned for inspection prior to guard duty. He always put an effort into making the Colonel’s Orderly, not to earn brownie points, but to earn a three-day pass by making Colonel’s Orderly three times. And you got to sleep in your own bed and not in the guard shack.

Stickpin shows the location of Footloose Forester's barracks room in 1962-63, at Fliegerhorst Kaserne near Langendiebach, Germany. The post was a Luftwaffe base during World War II.

So, he earned at least four 3-day passes for Colonel’s Orderly; one for Soldier of the Month; one for Driver of the Month; one each time our small special weapons section passed a major inspection; one each time he was an Honor Graduate at some training program; one for being the Outstanding Soldier of the Cycle at basic training; and so on. In all, he enjoyed 22 three-day passes in the Army; and for that everybody despised him. The nice thing about the Army system was that a 3-day pass meant that you got Friday, Saturday, and Sunday off; or Saturday, Sunday, and Monday. They set it up that way as an incentive; and they honored the system, even if virtually everybody grumbled that he always seemed to be on a pass, if not on his 30-day-per-year annual leave.

When he was in advanced training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, he gambled that he would later be sent to Europe. He wanted to save his annual leave for Europe, so he declined to take a permitted leave after training was completed, as most soldiers did. He also declined to take leave after basic training at Fort Ord in California. Thus, when he arrived in Langendiebach, Germany for an 18-month tour of duty, he had 60 days of annual leave at his disposal, plus the 60 days of earned 3-day passes that he continued to add to his intended travel kit. Traveling in Europe was great fun. The Army years were fun, even if the Army wasn’t so much fun.